Nihonbashi is full of pigeons

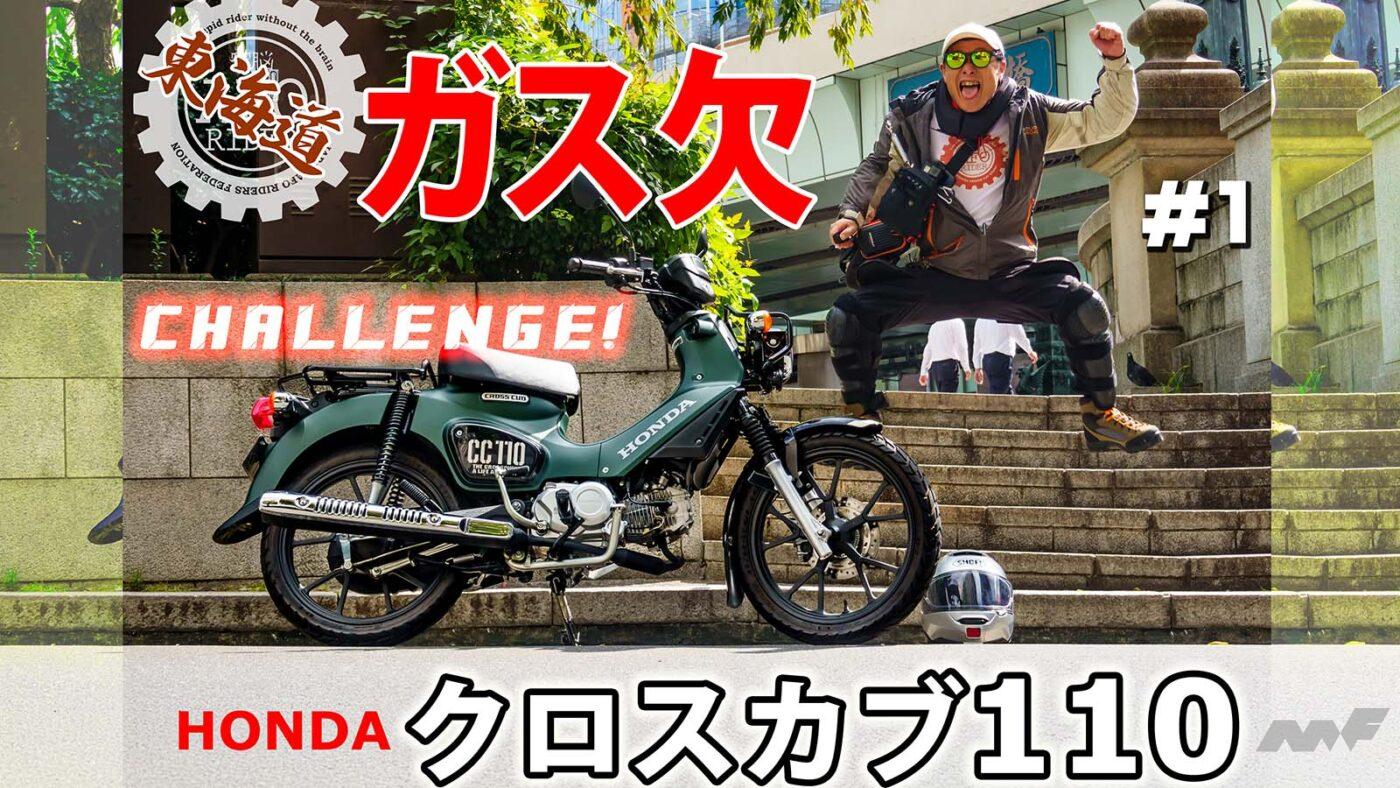

My companion on the Tokaido journey was the Honda Cross Cub 110. This machine retains the sturdy and reliable ride of a Cub, but with a cute design.

Many Japanese people have a misunderstanding of the children’s song “Hato Poppo.” When asked to sing it, most people will cheerfully start singing along with “Poppopo~ Hato Poppo~♪,” but this is the height of stupidity. This is because they’re singing the wrong tune. The well-known song is actually a children’s song with a different title, “Hato” (author unknown). The real “Hato Poppo” (music by Rentaro Taki, lyrics by Kume Azuma) begins with a deep bass note that resonates deeply in the stomach: “Haato poppooooooooooo♪.” A quick search will help you sharpen your rusty intellect.

Nihonbashi was once again an area filled with pigeons.

Now in its eighth installment, the relentless “Tokaido Gas Challenge” is a hands-on report that follows a journey from Nihonbashi to Kyoto, continuing along the Tokaido until the gas runs out. My partner on this gas-starved journey is a Honda Cross Cub 110. I filled up the tank and reset the trip meter to zero. Leaving Nihonbashi, which was covered in pigeons, behind, I headed west along National Route 1 in Tokyo.

The Cross Cub 110’s meter is plainly simple, but it is equipped with all the necessary features.

The area around Nihonbashi is a forest of dull buildings.

The versatile Cross Cub 110

The Cross Cub 110 is equipped with an air-cooled, 4-stroke, SOHC, single-cylinder, 109cc, 8.0PS engine. The transmission is 4-speed, the overall length is 1935mm, the overall height is 795mm, and the vehicle weight is 107kg.

The English word “crossover” means “to go beyond the boundaries or boundaries of things.” In automotive terms, “crossover” means something like “a vehicle that is primarily intended for everyday use but can also be used for multi-purpose purposes such as off-road driving.” The Cross Cub 110, which bears this name, is a versatile Cub that is both a casual city Cub and can also be used for adventures in the mountains and fields; it is a light “outdoor Cub,” so to speak.

Perhaps because the leg shield, which is a symbol of the Cub, has been omitted, the front and rear views have almost no Cub-like feel.

Cross Cub vs. Hunter Cub

This is the CT125 Hunter Cub. Its air-cooled, 4-stroke, SOHC, single-cylinder, 123cc engine produces 9.1 PS. This is only 1.1 PS more than the Cross Cub 110, but the difference in ride feel is greater than the numerical difference.

When it comes to outdoor-themed Cubs, some people may think of the Cross Cub and the Hunter Cub, which look very similar. People who aren’t familiar with motorcycles may confuse the Cross Cub and the Hunter Cub. Takahashi himself didn’t bother to distinguish between the two until he found himself in a difficult situation where he had to ride every bike he could find and write test ride reports on them in order to stave off his daily hunger. Both have similar designs, so he lumped them all together as if they were the same type of Cub and didn’t pay them much attention. In the first place, there’s no need for the average person to distinguish between them.

The engine of the Cross Cub 110. The shifter is a constant mesh 4-speed return type (although it is a rotary type when stopped), and it is equipped with both an electric starter and a kick starter.

However, even though they look similar and are outdoor-oriented, the Cross and Hunter Cubs are completely different vehicles with completely different riding experiences. Roughly speaking, the Cross Cub is a “stylish version of a soba restaurant bike,” and the Hunter Cub is a “sports bike in the shape of a Cub.”

While it doesn’t really matter to most people, those who are considering buying an outdoor-oriented Cub should at least be aware of the differences.

The charming round LED lights are surrounded by headlight guards.

The Cross Cub’s greatest feature is its simply adorable design. Its round, curly body exudes a charming, almost voluptuous look, somewhat reminiscent of a friendly small dog. Even the round pipe headlight guard, an icon of the Cross Cub that exudes an outdoor feel, lacks any intimidating qualities and is as adorable as a playground piece. While both are outdoor-oriented, it stands out in stark contrast to the Hunter Cub’s serious, heavy-duty design.

The front is equipped with a hydraulic disc brake with ABS, and the rear is equipped with a mechanical leading/trailing (drum) brake.

The driving characteristics are also different.

The Cross Cub equipped with a 110cc engine is almost identical to the standard Cub in terms of driving. Although it has been refined to have a precise ride with minimal bounciness, the overall driving feel can be described as that of a regular Cub.

On the other hand, the Hunter Cub is equipped with a powerful 125cc engine. When you twist the throttle, you feel a slight surge of power that makes you wonder, “Is this really a Cub?” It’s a sporty machine that allows you to enjoy quick driving supported by a stiff suspension.

The feeling of riding on it is just like a Cub. The Cross Cub 110 is light and easy to reach the ground, making it a machine that anyone can easily ride.

The Cross Cub is recommended for those who want a bike that is easy to ride and has the relaxed feel of a Cub, and is easy to use every day, and has good maneuverability, such as “I only ride it to school, but I’d like to go on tours every once in a while,” and prioritize everyday use.

On the other hand, the Hunter Cub is recommended for those who want to enjoy hardcore sport riding, but also want a bike that can be used as a commuter, such as “I want to ride forest roads and go stream fishing once a week, but it would be nice if I could commute to work at the same time,” and are an outdoor-oriented person.

It’s difficult to follow the old Tokaido road in Tokyo. Just getting out of the dingy, building-filled streets is a struggle.

It looks good even on the congested streets of the city… but that’s to be expected when you consider that it was originally a practical Cross Cub.

Enoshima is in sight, Takahashi’s house is far away

The atmosphere of Fujisawa-juku on the Tokaido still remains around Yugyojizaka.

After leaving Tokyo on National Route 1, it’s a smooth ride west through Kanagawa Prefecture, switching onto National Route 16 or similar. Near the border between Yokohama and Fujisawa, National Route 1 branches off into Kanagawa Prefectural Route 30. The endless, boring, building-strewn roads from the center of the capital start to feel a bit more like a journey from this point on. Switching to Prefectural Route 30, I head for the coastline. It would have been quicker to head straight to Tsujido Beach, but the bright, clear weather tempted me to drop by Enoshima.

The road to Enoshima is jammed with traffic, whether it’s tourists or locals.

I’ve passed through this area many times and have seen Enoshima from the coast, but I’ve never been to the island. I decided to cross the bridge and go ashore, but it was just an ordinary little island with a row of souvenir shops, no earth-shattering thrill rides, and no charity concerts by Southern All Stars.

The road to Enoshima is quite fun, but once you get there it’s not so much fun.

The anime mecca is packed with people

The state of the sacred place in “Slam Dunk” reminds me of that famous line: “Haha, look! People look like garbage!!” (Huh? Isn’t that from this anime?)

Many recent anime series have taken the trouble to depict real-life landscapes within the story to create so-called “sacred sites.” Near Enoshima, there’s even a sacred site for the anime “Slam Dunk.” I heard the railroad crossing in front of Kamakura High School Station was the sacred site, so I went to check it out. It was a hellish scene, swarming with tourists and security guards honking their whistles.

“Slam Dunk Imagination” I only glanced at the manga about 30 years ago, so I don’t know the characters or the story, and I don’t really know the basis for the sacred place ♪

Unfortunately, Takahashi has never seen “Slam Dunk.” From what he hears, it’s based on a popular teen-themed manga about a group of basketball-loving boys. However, with only that level of knowledge, to Takahashi, this sacred site unfortunately looks like nothing more than a railroad crossing. It’s not just anime, but most religious sites are likely to shine as pure and sacred only in the eyes and hearts of their core believers.

The platform at Kamakurakokomae Station is packed with what we assume are anime fans.

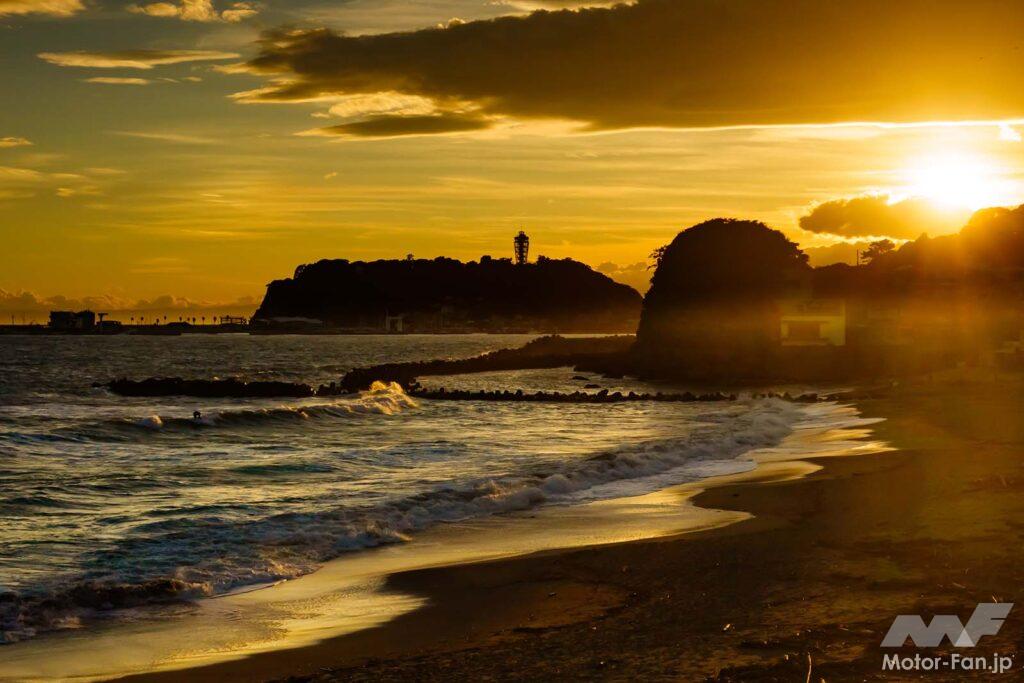

The sun sets over the Shonan Sea

A little way from the holy land, the fuel meter started to move for the first time. One mark had gone down out of the six, leaving five marks. The trip distance was 66.8km.

We head west, glancing at Enoshima, its silhouette floating in the dazzling sunset.

The view of shitty Shonan, blessed by a shitty sunset, is so shitty it’s disgustingly beautiful.

Leaving Enoshima and heading towards Tsujido Beach, the number of tourists has drastically decreased, making it quieter.

Unfortunately, however, the sparsely populated beach at dusk is prone to the emergence of pests that mar the beautiful scenery. These are the so-called Abekkies, a pair of men and women who are unnecessarily flirting and showing off their intimacy. What’s more, the area is not only home to domestic Abekkies, but also to inbound tourists.

For Takahashi, Tsujido Beach has recently turned into a terrifying, glittering, foreign-owned Abecchi area. It’s seriously annoying, madness!! (Even that reaction is already in the style of a Showa-era manga!) (Even the ending of the sentence is in the style of a Showa-era manga)

Takahashi and his Cross Cub arrive in Tsujido as dusk approaches. There’s no point in staying too long, as they risk being overcome by their complexes and dying.

Coastal Night Trip

We headed to Hiratsuka through Shonan as the sun set.

I dug my toes deep into the sand at Tsujido Beach, kicked them back, and left the Shonan coast, practically kicking sand up with my hind feet.

I tore through the lukewarm night air and headed for Hiratsuka. I parked my Cross Cub in the parking lot in front of the station, climbed into a room at a nearby inn, ate some convenience store food, and promptly fell asleep.

I unpacked my luggage in front of Hiratsuka Station.

The trip was 84.2km, the same distance from Nihonbashi, of course. Before I knew it, the fuel meter had dropped by two marks, leaving four marks.

[MAP] Tokaido Gas Challenge #8 Honda Cross Cub 110 [Nihonbashi to Hiratsuka]